Law Society Bencher Election 2019: City of Toronto Electoral Region - Wyn with Selwyn Pieters

"Vote Pieters In as a Law Society of Ontario Bencher. He'll Never Peter Out

I am competent, committed, and collaborative advocate who is interested in serving as a Bencher in the interest of us members and in the public interest. Vote for me in the Law Society of Ontario Bencher elections. I am not a rubber stamp. I will fight for the interest of Ontario lawyers and ensure accountability.

I am interested in working on the following issues:

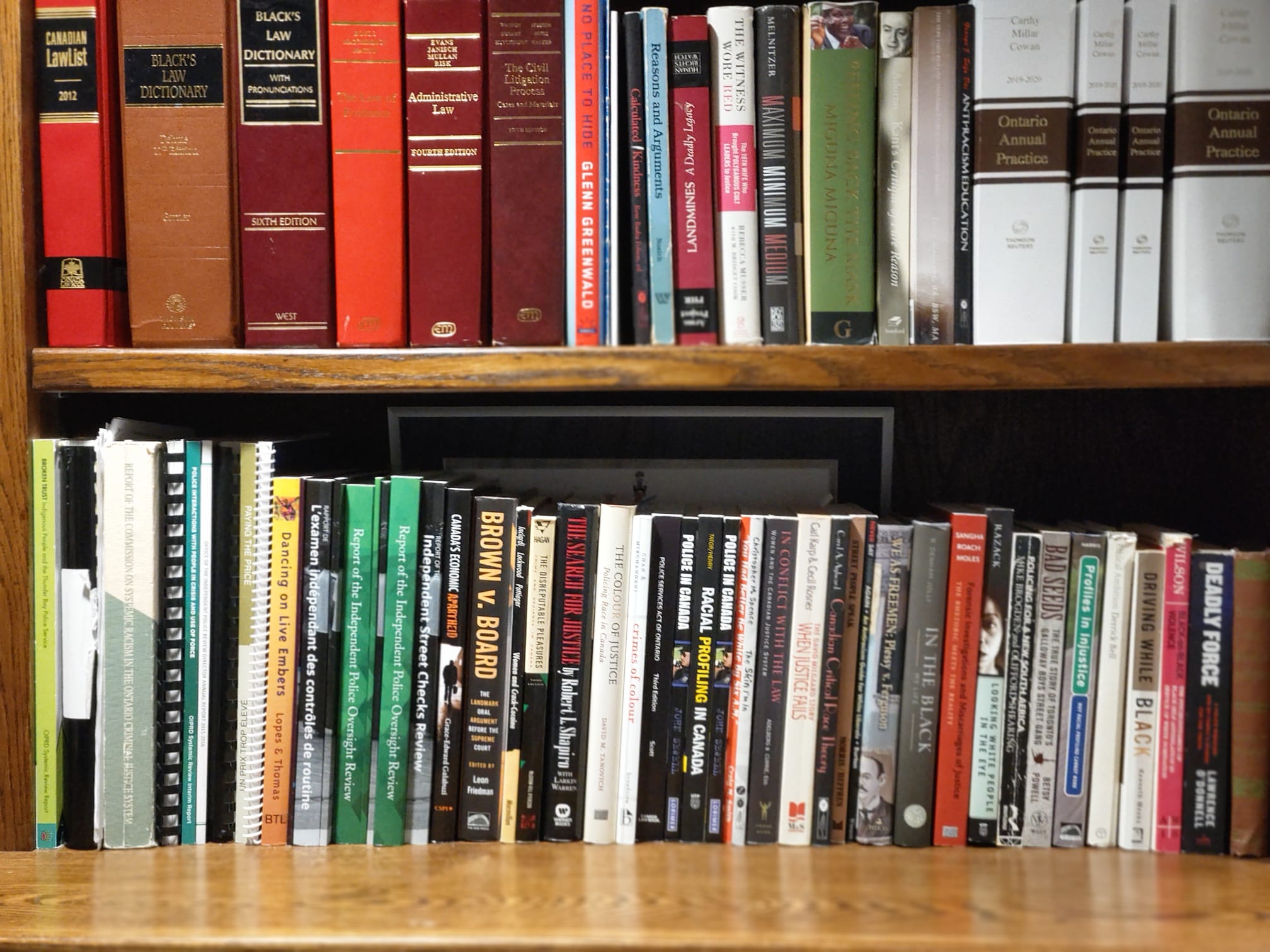

My legal work has always been conducted with strict adherence to the principles of societal equity, with the goal to nudge society further towards this ideal with every legal case. From February 2005 to present, I have been the Principal Lawyer and Owner of the Sole Proprietorship, Pieters Law Office, an international law practice with current operations in Toronto, Canada; Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago; and Georgetown, Guyana. I have extensive legal experience in a number of areas including Human Rights, Criminal Law, Employment Law, Administrative Law, Immigration Law, Civil Liberties Litigation, Constitutional Law and Alternative Dispute Resolution. As will be seen from the hundreds of reported cases on a wide area of law, I have extensive trial work at both the provincial and supreme court levels, appellate experience at the Federal Court of Appeal, Ontario Court of Appeal and Supreme Court of Canada, administrative Law Experience at numerous administrative tribunal and significant experience working with youth including homeless, marginalized, gay, racialized and Black youth.

I have also provided legal counsel to many advocacy organizations such as The Black Action Defense Committee, Dr. Roz Healing Place, Association of Black Law Enforcers and Jane and Finch Community Organization on a diverse range of projects including legislative and justice sector reform such as the Safer Ontario Act and Carding; Law Enforcement issues including racial profiling, representing the organizations in deputation to Committees, Police Services Board and Inquiries; human rights, and access to justice, race and gender-based violence and public legal education.

I understand the ethics and professionalism associated with the legal profession and this is consistently reflected in my approach to my work. Even in my personal life, I made the decision to go beyond fighting the injustices experienced by my clients, but to also seek redress when I myself suffer similar indignities, regardless of the consequences for seeking this reparation.Systemic, Institutionalized and Unconscious Racism in the Legal Profession

Black, African-Canadians, have been historically and presently been admitted to Law Schools in very small numbers. The gatekeepers are doing a great job of keeping us out of the profession and when in the profession segregating us. How many Black male and female lawyers are partners in the seven sister's? We can still count them as they are very few. We have fought to retain our dignity in the face of historic disadvantage, systemic discrimination, legally sanctioned discrimination, and other forms of oppression and repression of African Canadians.

I experienced first-hand the possibilities of the justice system in allowing for aggrieved persons to receive justice, when I made the decision to challenge the racially motivated treatment I experienced, such cases as reported include:

Interrogating Racism in Legal Spaces

Stereotypical Identification of Black Men as accused Person is Typical in our System of criminal (in)justice. Those who disagree has not walked in my shoes so cannot persuade me otherwise. Here is an encounter at Old City Hall for which I had to educate the Crown lawyer.....

'I am a Black male who is a Barrister & Solicitor. I write with respect to your conduct this afternoon in courtroom 111 at Old City Hall... I had signed in on the Counsel sheet representing an accused person (Male, White, 32, blue eyes, brown hair). I then sat in the counsel area directly behind you waiting for the case to be heard. This was a matter that was screened for diversion as it was a theft under from LCBO $12.95 bottle of Liquor

When you stated to the Justice of the Peace that there were no more counsel matters, without me hearing you call the matter for which I was providing representation, I stepped forward from counsel area to alert you to the fact that there was indeed one more counsel matter. Instead of listening to me, you pointed to where the unrepresented accused persons were and directed me to go and join the line. I had to remind you that I am a lawyer. You did not even apologize. I have been in courtroom 111 where you were crown on numerous occasions and I was very shocked, surprised, embarrassed and in some way humiliated by your behavior. All you had to do if you were not sure whether or not I was a lawyer is ask the question, not assume I am an accused person who should join the back of the line."

You may or may not know that Black male lawyers are fed up being treated as though they are accused person when practising before the courts......"

I believe there is a need to record today's incident because it reinforces certain stereotypical attitudes and notions that indeed results in racial profiling."

Peel Law Association - Lawyer's Lounge

Progressive racialized and non-racialized members of the LSO knows that there is not only racism in the legal profession itself but that racism also affects how racialized lawyers, particularly those who are Black and male are treated. See, for example, Peel Law Association v. Selwyn Pieters and Brian Noble, 2013 CarswellOnt 7881, 2013 ONCA 396, 228 A.C.W.S. (3d) 204, 116 O.R. (3d) 81, 306 O.A.C. 314, 9 C.C.E.L. (4th) 233, [2013] O.J. No. 2695(Ont. C.A.), a racial profiling case involving two Black lawyers and a student, two of whom had dreadlocks.

Racism continues today as part of our everyday culture, and as a convenient ideology for maintaining cheap labour provided by people of colour and Black people. . . . the ideology of racism has, in post-slavery and post-colonial days, still resulted in the over-representation of Black workers and workers of colour in the least desirable, least secure, poorest paid segments of the workforce. Simultaneously, they have been excluded from better paid, secure, more desirable jobs through systemic practices in the labour market . . . The labour of people of colour and of Black people is assumed to be "natural", "unskilled", and therefore inferior . . . [Tania Das Gupta, Racism and Paid Work, (Toronto: Garamond Press, 1996), at 1-40, esp. at pp. 14-5]

The Law School Admissions process - a success story after fighting to get in

In the legal arena, I still question why it is that difficult for Black males to be admitted to the Law School. I had to fight and fight hard to get into law school. I launched a challenge to the challenge to the LSAT and its use in Ontario's law schools, on the basis the LSAT systematically discriminates against Black, African-Canadians. The studies showed that Black consistently scored lower in this test. I filed complaints with the Ontario Human Rights Commission, asserting that my equality rights had been violated because I had been refused admission on the basis of not meeting the cut-off score on the Law School Admission Test (the "LSAT"). My position as and it remains to this day that the LSAT is an arbitrary and irrelevant measure of merit. My success through law school, Bar admissions, articling and the practice of law is a testament to this. It was only through litigation that I believe I was admitted to Osgoode Hall Law School. See, Pieters v. University of Toronto ONSCDC File # 274/02, April 14, 2003, reported at: 2003 CarswellOnt 1331, (2003) 170 O.A.C. 180, (2003) 226 D.L.R. (4th) 152, (2003) O.J. No. 1316 (S.C.J.). My call to the Bar was featured in the National Film Board of Canada's Momentum program that produced a documentary titled Selwyn by Bryan Friedman described as "a story of one determined young man who fought his denial of admission to law school, was finally admitted, successfully passed, graduated, completed bar ads, articling and was called to the Bar." This documentary was aired on CBC Newsworld on Wednesday, April 20, 2005, 10:00 p.m., shown on the documentary channel and presented at various film festivals.

Law Society of Ontario's Statement of Principles

Lawyers are governed by the Rules of Professional Conduct, the Human Rights Code, the Solicitors Act and a complete regulatory scheme of which the statement of principles are a part until revoked or repealed.

In Law Society of Upper Canada v. Selwyn Milan McSween, 2012 ONLSAP 3, a case that involved professional misconduct findings against McSween by a Law Society of Upper Canada hearing panel, in concurring reasons, adjudicators Clayton C. Ruby and Constance Backhouse examined McSween's personal background, antecedents, training and the nature of discrimination and wrote the following, which though lengthy deserve quoting liberally:

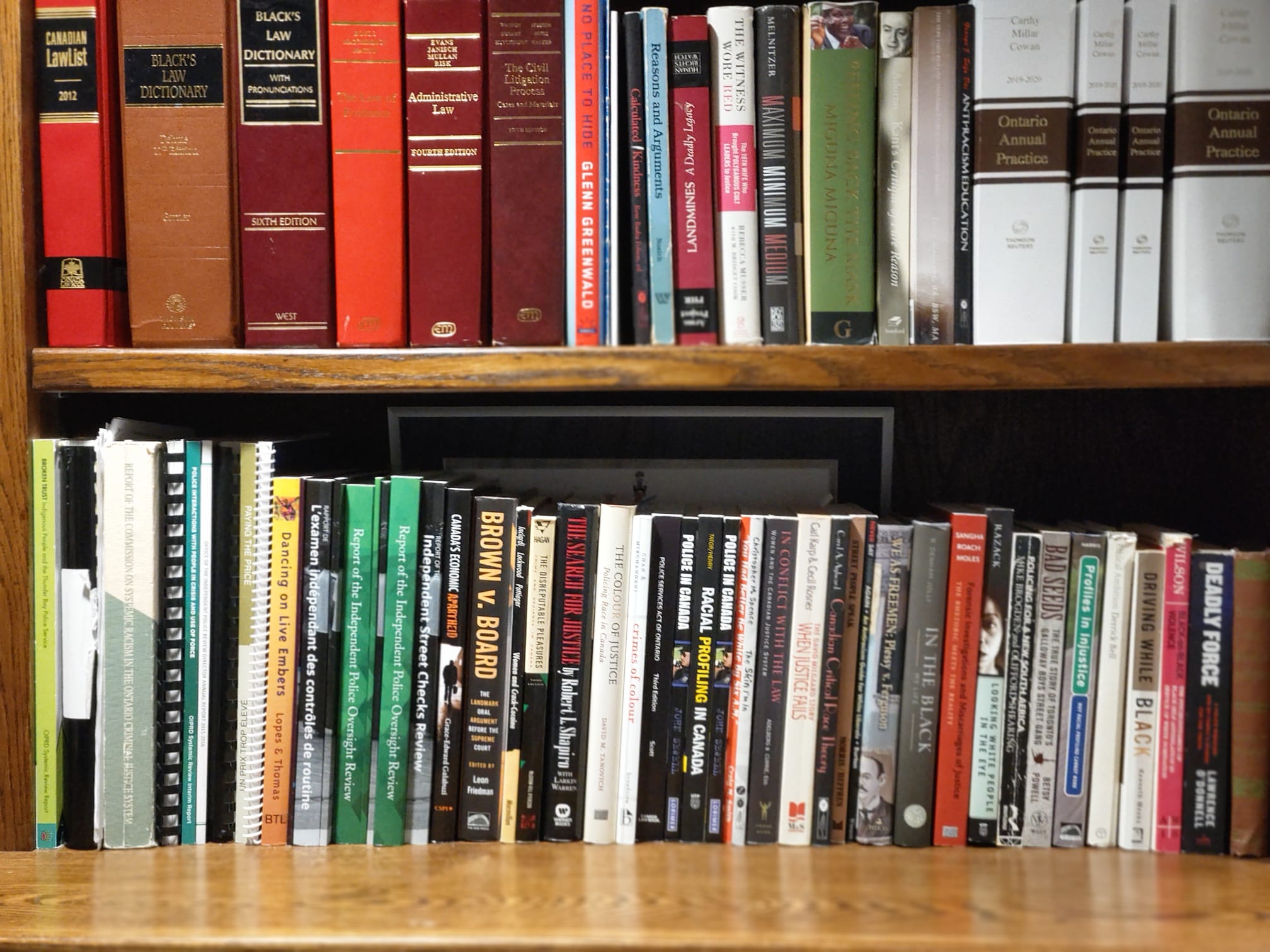

3. Racism in the Context of Law[68] In 1999, the Working Group on Racial Equality in the Legal Profession of the Canadian Bar Association published Racial Equality in the Canadian Legal Profession. The report examines racism in the legal profession and reveals that students from racialized communities have fewer opportunities to secure articling positions and first jobs. They do not benefit from the same articling experience as their non-racialized colleagues who are introduced to clients, assist more senior lawyers on important cases, and who conduct research on a broader range of files. There is no evidence to suggest that circumstances have changed for the better; in particular, articling opportunities have diminished. See: Working Group on Racial Equality in the Legal Profession, Racial Equality in the Canadian Legal Profession (Canadian Bar Association: Ottawa, 1999).

[69] More recently, in 2004, the Law Society commissioned a study entitled Diversity and Change: The Contemporary Legal Profession in Ontario. This report attempted to establish a baseline for tracking diversity and equity in the Ontario legal profession. It found that, when surveyed, lawyers of racialized communities are more likely to reveal that they were denied opportunities to take responsibility for cases because of client objections, and they also were more often subject to inappropriate comments by judges and other lawyers. See: Kay, F. M. et al. Diversity and Change: The Contemporary Legal Profession in Ontario (A report to the Law Society of Upper Canada) (Queen’s University: Kingston, 2004).

[70] It is reasonable to infer that as a group, Afro-Caribbean Canadian lawyers are economically and professionally disadvantaged when compared with their colleagues, and that many face diminished opportunity as alleged in this case by Mr. McSween.

[72] The research into Canadian legal history shows that systemic racism has had a substantial impact on the legal profession. It demonstrates that ideas of legal “professionalism” have been used to exercise power and exclusion based on gender, class, religion, and race. The first minority individuals who sought admission to the legal profession faced significant barriers. Those who succeeded in obtaining entry found that those barriers continued to impact upon their careers when they attempted to practise. Significantly, an increased risk of disbarment was one such barrier for racialized lawyers.

[73] It would be misguided to be aware of this history and yet ignore its contemporary incarnations simply because the legal profession has today become much more diverse. The legal profession has made no concerted effort to rid itself of the racism inherent in the practice. As the evidence in this case illustrates, racialized lawyers continue to face barriers not experienced by their colleagues.

In Law Society of Upper Canada v. Terence John Robinson, 2013 ONLSAP 18 following from the principles in McSween, an appeal panel observed that:

[78] In our view, McSween supports the proposition that systemic racism and discrimination which explains or provides context to why a licensee engaged in misconduct or conduct unbecoming is relevant. This is not unique to Aboriginal licensees. What is unique are the systemic and background factors that affect Aboriginal people, including Aboriginal lawyers and how these factors have affected them.

We need action, not self-serving words. The dismal and shameful record of the treatment of Black, African Canadians and Native, Aboriginal Canadians lawyers speaks for itself.

Conclusion

At its core my work shows me as a fair, fearless person with immense integrity. I am for positive and transformational change at the Law Society of Ontario. It is for these reasons that I believe that I can be your voice as a Bencher.

I can be reach through the following platforms:

| Selwyn A. Pieters - Barrister & Solicitor; 2021 All rights reserved. |